Violinist Hector Scott shares how bad practice habits can create the illusion of progress, and offers solutions to break the cycle

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Unpredictable repeatability is a powerful behaviour pattern that can reinforce short term rewards at the expense of long-term growth. Termed the Three-part Behaviour Loop by Michael Easter, this loop is comprised of opportunity, unpredictable rewards and quick repeatability. It is used in every facet of our lives, such as social media, sports betting and snack choices. We are inherently attracted to behaviours that fall into this loop. We play a phrase, and it is full of mistakes or broken connections, so we immediately play it again. It is still poor but maybe we are rewarded with one connection that had failed before, suddenly working. The unpredictable reward! So, we immediately play the phrase again and a different connection works although the previous one might fail again.

Opportunity offers us the chance to gain something of value, however, the unpredictable nature of acquiring what we value drives us towards actions which are quickly repeatable and offer a sense of movement towards complete success. With each repetition of a musical phrase, a section here or there does become smoother, and we may conclude that our practice is productive, and our learning is effective. Parents and teachers say, ‘You’ve almost learnt the piece!’ Although the ‘near miss’ approach, in which we repeat actions with increasing degrees of approximate success, may be advantageous in certain circumstances, learning a string instrument requires a more considered approach.

Initially, we must recognise that we are intrinsically hardwired to this behaviour, an evolutionary response to a distant past in which many of life’s securities such as food and shelter were indeterminate events. Developing an awareness of this natural tendency while showing ourselves humility and avoiding frustration is key to transforming the behavioural loops which can limit the value of our practice. Our second task is to consider shifting the opportunity set beyond simply learning a piece of music such as Bach’s Chaconne. We can consider the relationship between harmony and our chosen sound quality, or the connection of dance to the explored themes, or the contrasts in interpretations offered by musicians working in the modern and historically informed traditions. As a consequence, a unique range of possibilities and rewards may become evident through the degrees of expressive freedom available to a young musician. Essentially, the work of Bach is the means through which we creatively invent new ideas with increasing expressive fluidity. Slowing down our practice is integral to this process. We are less likely to repeat unpredictable behaviours which are engineered to keep us in a comfort zone of controlled challenges and give us the illusion of dedicated application to our values.

Practice makes perfect. Be careful what you practise.

A second key consideration is the comfort. Today’s world is more comfortable than at any other time in history. However, leaning into discomfort, having experiences which move you into the unfamiliar or uncomfortable, can give rise to a new perspective. As a species, we have evolved to do the next easiest, most comfortable thing and we have applied technology to our environments to aid us in our efforts. We run on treadmills or lift perfectly balanced weights in air-conditioned studios in our invention of exercise. Exercise is something we invented when we engineered movement out of our lives. When you run on a treadmill staring at a screen, you do not need to do much cognitive work. When you consider the historical context of physical activity, exercise encompassed far more than the physical work of moving your body across the land. The breadth of skills ranged from an acute physical awareness of hydration, foot placement and hunger to an external awareness of environmental threats and the tracking of prey. We are unaccustomed to such complexity. When we bring ease into our practice, we can struggle to engage with the sensory and wide range of energies and factors that we need to consider.

All children are born artists. The problem is to remain an artist as we grow up — Pablo Picasso

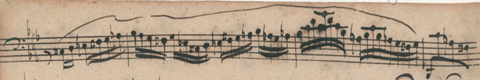

To bring a healthy degree of unease into our learning, practise in different physical positions such as while sitting on the floor, sitting on a chair, and standing. Try playing without the scaffolding of a shoulder rest, chin rest, or cello spike to explore instrumental balance. Hang a light weight from your scroll to develop an awareness of the instrument and when the weight is removed, the freedom of instrumental movement will be enhanced. Now explore how the violin can be brought to the bow to create different sound qualities. Play from a score to develop a wider appreciation of the musical dialogue or play from the original manuscript to engage with the information imparted by the composer’s calligraphy that is designed to inform the performer how to play dynamically.

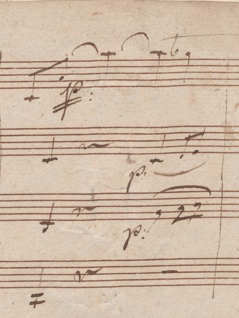

Consider, for example, the slur in Bach’s Cello Suite no. 4 that David Watkin suggested might indicate ’a quasi-improvised flourish under one bow’ or Beethoven’s dynamic markings with lines that Nicholas Kitchen suggests might indicate degrees of expressive intensity.

When considering the intimate relationship in dialogue between the voices, these subtle gradations in emotional intensity offer the performer the opportunity to explore interaction in a new way. Dance was an enormous part of life in those days, and we have lost the sense of its meaning both socially and personally to people at this time. The dynamic gradations between pianissimo and piano, indicated by ppmo, pp with two underlines, pp with one underline, pp, p with two underlines etc., suggest subtle changes in intensity and volume that reflect Beethoven’s complex imagination of sound. As a performer these variations of expression require us to consider how we explore our own sound world. Do we use vibrato, or bow speed, point of contact, or pressure. Are we whispering with agitation or anticipation or exhilaration? How do these fine nuances affect the complex layering of sound within an ensemble? This allows individual performers to respond to one another with a sense of renewed understanding and degrees of intimacy and connection. To put this across effectively, as a performer, we must care intensely about sound quality and develop a profound sense of connection physically with your instrument that allows you to explore a wider expressive range.

We are unaccustomed to playing from an original score or manuscript with unclear markings and distinctive script, and we are challenged to understand the harmonic journey of the composer rather than simply follow the path presented in a clean Barenreiter copy. A sequence leads a performer somewhere and can be viewed as representing the leaves of a tree. We can recognise them by their basic shape as belonging to a particular variety such oak or maple, but each leaf is subtly different in terms of size, colour, depth, and shape. When understood like this, the performer might respond to the different keys that the sequence passes through in much the same way as a Mondrian painting where one colour communicates with another to produce an emotional consequence. As a performer, we are elevating our technical capacities through exploring our imagined musical intentions. Looking and understanding a score as a composer, performer, improvisor is vital in connecting and integrating a scores information.

However, we lack opportunity to be thrust into positions which aid us in realising the possibilities. For instance, how many music colleges offer modules where their students administrate, devise, and present a week’s music programmes to diverse audiences from prisoners to dementia patients, from secondary schools to special needs schools? The experience might be challenging but the results will be life changing both emotionally and practically. Then, the next call to adventure might be to interact with other musicians from diverse backgrounds such as Govan’s ‘Musicians in Exile’ and share ideas, skills, and cultures. The Silkroad project demonstrates the extraordinary potential of connection and shows the real story of human and musical improvement, rather than the yearly performance assessment of Mozart A major concerto with accompaniment rendered on a Steinway Grand in an air-conditioned architecturally designed hall with beautifully balanced acoustics. In having less resources and greater challenge, we are forced to do our best work because the situation drives us to first principles. We innovate and become more creative.

Creativity now is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status — Sir Ken Robinson

Our schools, colleges, and universities often teach us, whether through design or through unintended consequences, to live in our comfort zone. It is nice, comfortable, and safe but we do not explore the edges, and this limits us over time. The fact that we have educational league tables is a symptom of this status quo, but it should be through education that we explore a future we cannot grasp. Are we overlooking something? Embracing what might be difficult is ultimately the human journey and is key to our wellbeing.

You risk so much hesitating to fling yourself into the abyss — Anon. Cistercian Monk

Read: Challenge your curiosity and your preconceptions: violinist Hector Scott

Read: How to unlock hidden potential: Redefining progress and the problem of procrastination

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet