Violin and viola teacher Martin Goldman took up swimming during the pandemic. He writes about how the process made him step into the role of the student and how the physicality of swimming can be transferred into teaching stringed instruments.

The pool in Kapala, a beach community south of Lima, Peru, was unheated. After nine months of homemade meals and stockpiling toilet paper, my wife decided to invite her daughter and family for a beach vacation. It was the end of December.

I befriended the swim instructor and set a goal of swimming 50 consecutive laps. At 25 metres, that would be more than a kilometre. Having begun my swimming regime in Florida, I’d already reached several milestones. Once beyond twelve laps, twenty was surprisingly easy. From there it was more about how much time I wanted to stay in the water. The goal was four styles: breaststroke, elementary backstroke, freestyle, and standard backstroke.

This aquatic journey started with two herniated disks; my personal overture to Covid-19. It robbed me of nearly six weeks of sleep. By the time I got to Peru, I was still a crappy swimmer. The new drill was getting to the pool every morning by 8am. The challenge was physical as well as emotional; at 73, doing something new was daunting. I became obsessed to execute each stroke elegantly, and with force.

As if by instinct, I counted laps and strokes, measuring each breath like the counting I do when I play and teach. Over time, my body seemed to intuit if I miscounted. Teacher and student had converged. I kept repeating the mantra I drill into my students; ’thoughtful & purposeful.’ Would the process allow me to be a better teacher?

I assigned myself the first four laps as warm-ups, to get the equipment activated, like etudes and tonalisations I preach after tuning and putting on rosin. I scrutinised every detail as I swam, fixing as best I could along the way. Warm-ups, done slower and without jerky movements, let me release the big muscles. The elementary backstroke had me feel how light my arms could be sitting on the water, stretching back as straight as possible. If I pushed too hard or went too deep, I moved slower. The water invited me—sink, or float. I became sensitised to the pushback, like the strings and sizzle of bow tension; a gratuitous form of energy. I thought about bow speed and the sweet spot, between the bridge and fingerboard.

Not holding tension, whether breath or muscles, seemed to mirror legato and détaché, that special articulation in everything Baroque—even up-bow spiccato in von Weber’s Country Dance. Though each day brought some success, there was still frustration over time; how long do I need to let go of the tension? As with my students, I had to guide myself into discovery. And that led to a harsh realisation: I was tightening my stomach muscles, all the time.

When I swam backstrokes, staring at the sky and daring my head to float; it felt unnatural to let go. A student came to mind, whose head was constantly tilted to the wrong side. I had to believe it would work, not give up. Like the bow arm, all strokes are connected to arm weight.

I was putting off breath control and nervous breathing. The anxiety was palpable from the beginning, like being unwilling to keep the left elbow tucked in or the right shoulder from rotating. I focussed on how to exhale, empty the lungs, feel my body expand, executing a surge of what I imagined could have been down and up bows—and releasing my stomach muscles.

It was clearly flight or fight, primitive brain, that invited moments of panic halfway through a freestyle lap – my face in the water, panicky to reach the end of the pool. Aware that string players rarely focus on breath, I considered a teaching moment: after the pandemic, I would like to ask a singer, dancer, and yoga instructor to bring their best angles of breathing to a group class.

Teaching myself to sense the lane dividers brought me to the ‘straight bow’ crusade. Looking meant putting my body out of alignment, like when students lean forward to get closer to the music stand, and their violins droop. I let my fingers relax into what my students know is the ’sleepy hand’ bow position, while pushing the water in each direction, feeling the flow between slightly open fingers. I struggled with swimming too fast, on top of the water, feeling the energy in my palms. Could that also be the three golden rules of the bow; speed, weight, and point of contact?

Change is incremental. I don’t respond well to sudden revelations, superlatives, or exaggeration. Taking the time to get comfortable with swimming as a cure, helped along by the irony of quarantines and lockdowns, made me learn more about myself. I was even relating underwater sounds to the prenatal world as I became familiar with the vagus nerve.

Before returning home to Miami, my last few days became the great fugue, my local coach conducting every entrance. As if each technical point was a thematic entrance, I was counting laps and strokes, how many breaths I could add to each exhale, how many kicks per stroke, and the number of kicks per stroke while keeping the knees from bending, sitting more on top of the water and cupping my hands. My breathing was deeper, exhales slower and measured, and my years playing viola, like counterpoint: ’It’s the neck, stupid. Release the neck.’

By the time I logged in my last 50 laps, it was a walk of triumph. Becoming the student, I reconnected to the teacher within. Teaching is both inward and outward; whatever we do to better ourselves, creates the potential for greater understanding and empathy.

An earlier version of this article appeared in The American Suzuki Journal volume #49.3

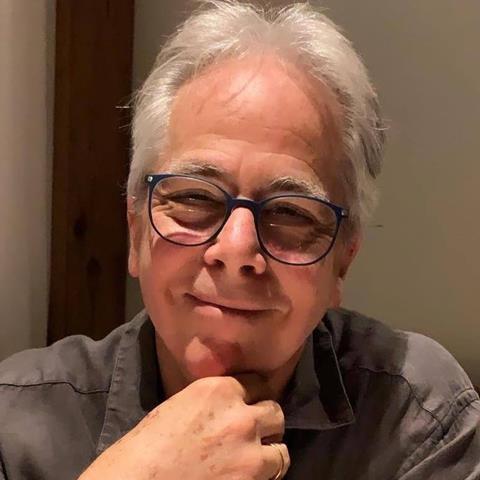

While at Manhattan School of Music in the 1960’s, Martin Goldman had the opportunity to be ‘a poet.’ He remained a violist/violinist. After a Masters degree from Yale and freelancing in NYC, he worked in Belgium, Italy and Puerto Rico. A Suzuki Method violin teacher going on 33 years, he now works in Miami, also writing picture books and adult novels.

Read: Scaling the walls: what musicians can learn from bouldering

Read: A video-gaming approach to practice will maximise your technical efficiency

No comments yet