Alberto Giordano reviews Claudio Amighetti’s magnum opus on the luthiers of north-west Italy

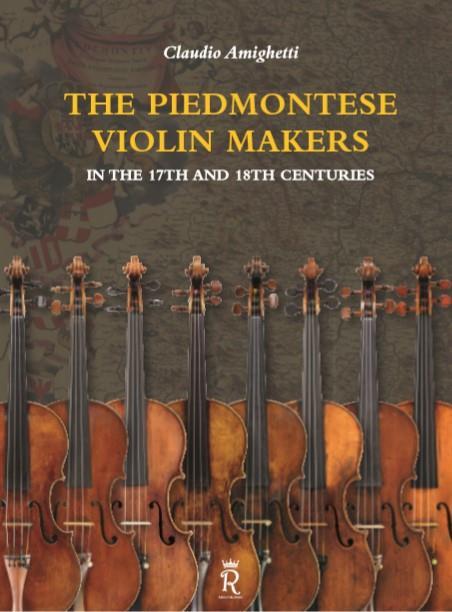

The Piedmontese Violin Makers in the 17th and 18th Centuries

Claudio Amighetti

275PP Rinko Publishing €260

In spite of the intensive research undertaken by scholars, collectors and violin makers over the past 30 years, the history of Italian violin making is still far from fully documented. Owing to the huge diversity of historical, political and social situations in the highly fragmented Italian peninsula, there are still many important areas whose lutherie traditions need to be clarified. Claudio Amighetti’s new book on the violin making school of Turin, from the Baroque era up to the time of the French Revolution, successfully fills the gap for this region. The volume is the result of 30 years’ research in the archives of Saluzzo, Turin and Savona: a quest indeed, undertaken with passion and patience, which unearthed a huge number of records on a wide range of makers (he has located 140 documents about Cappa alone!) within the two centuries investigated.

The book starts with an accurate historical introduction that describes the critical relationship between France and the Duchy of Savoy, the Thirty Years’ War in Italy and the Savoys’ aggressive policies to expand their territory. In his preface, John Dilworth notes the importance of the immigration of German violin makers to Italy and how they spread from Venice to Bologna, Turin, Genoa, Rome and Naples, leading the instrument making market. So the story begins, with Johann Angerer, one of the first recorded 18th-century violin makers in Turin, who was probably trained by his cousin Sebastian in Genoa. We then meet Enrico Catenar, probably a pupil of Angerer. Violin making in Turin was enhanced by the flourishing of musical life in the court, the passion of the queens regent for music, and the patronage of Vittorio Amedeo II of Savoy. The Music Chapel of the court had a key role in the development of music and the related business in Turin. It increased the importance of violin making, represented by luthiers including Catenar and Cappa, Giovanni Francesco Celoniato and his sons.

The historical profile of each luthier is described with an analysis of their individual making technique, with pictures illustrating the related features: in general, care has been given to the evolution of the local making technique, based on the use of a square-shaped channel in which the ribs were inserted, commonly used in areas of Central Europe, Flanders and the Austrian Tyrol. The selection of instruments comes mostly from important collections and museums from around the world. The quality of the pictures is sadly uneven owing to the variety of sources; a full photographic campaign was probably unaffordable. The book is well written and supported by meticulous research – the amount of original material Amighetti has compiled from the archives is quite a rarity in a violin making book. He points out honestly that this volume, rather than being a definitive work on the subject, is more of a starting point for future research: the result is an enjoyable read that fills an important hole in the history of Italian lutherie, and a great tool for learning the style and works of those less known and uncommon makers.

ALBERTO GIORDANO

No comments yet