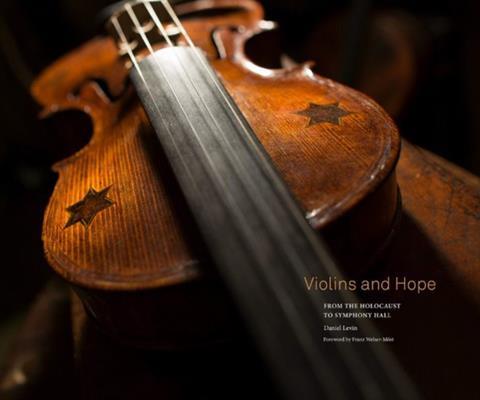

Violinist Raphael Klayman reads Daniel Levin’s well-illustrated account of Amnon Weinstein’s project to collect instruments made during the Holocaust

Violins and Hope: From the Holocaust to Symphony Hall

Daniel Levin

164PP ISBN 9781938086861

George E. Thompson Publishing $40

The unspeakable horrors and atrocities of the Holocaust, which left six million Jews murdered for no reason other than that they were born, need to be spoken of. Spoken, shouted from the rooftops – and sometimes sung. It may not be too well known that some concentration camps had music played for the amusement of Nazi officers by some talented interred Jews on various instruments, and in particular on the violin. A number of these players survived on account of their musical skill. After the camps were liberated, some of these musicians went on to good professional careers. Others could not bear to play music any more after the horrific associations that music and the camps had for them.

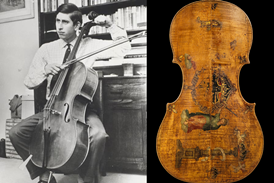

And what about their instruments? Did any violins survive? Were they of good quality? Would they have any meaning for us today, and could they sing again? Enter Amnon Weinstein, the distinguished Israeli luthier whose early training was with his father, Moshe, and who went on to study with Pietro Sgarabotto, Giuseppe Ornati and Ferdinando Garimberti. He had lost many relatives in the Holocaust and for a long time was at a loss as to how to process the tragedy. Eventually he found his calling: to collect, restore and draw attention to these violins, and to promote public performances on some of them. The project is called ‘Violins of Hope’. Many of these violins were inexpensive instruments but this was beside the point. Getting these violins to sing the best they could meant that Hitler had not completely succeeded in eradicating all Jews and Jewish culture. The Berlin Philharmonic once gave a remarkable concert with members of the violin section playing on these instruments.

Violins and Hope is a beautifully produced book. Large and heavy, with fine binding, thick paper and many gorgeous photographs, it may be called a coffee-table book in the best sense: one that anyone would be proud to display. Most of the story is told in the first quarter of the book, the rest being devoted principally to displaying and briefly commenting on the photographs. This makes more sense when we learn that author Daniel Levin is a professional photographer. Nonetheless, I would have preferred a more content-driven book. In fact, there is one such book, by James Grymes, which Levin himself highly recommends. Reading both books will certainly give a more complete picture of this subject.

Levin’s book is basically the story of a photographer who made a pilgrimage to Amnon Weinstein to learn about the latter’s project first-hand. One wishes that he had asked Weinstein about some basic violin terminology that might have avoided some awkward expressions, such as calling the belly a ‘face piece’ and either plate a ‘deck’. These quibbles aside, it is a lovely book on a most important subject. May these hopeful violins sing for ever.

RAPHAEL KLAYMAN

No comments yet