Startled by children’s ability to learn their own language, Shin’ichi Suzuki applied the ‘mother-tongue’ approach to violin teaching. William Starr explains the principles behind his then-revolutionary ideas in this article from December 1998

In 1964. I walked into a packed concert hall in Philadelphia during the Music Educators’ National Conference to hear a programme given by a group of Japanese children. Like most of the others there, I had no Idea that what I would hear that day, and what I would later learn about the work of Shin’ichi Suzuki would greatly influence me as a musician and as an educator.

It was my good fortune, soon after, to make an extended visit to Japan where I had the privilege of knowing the man Suzuki — not just his method’s doctrine but his simple, gentle, intense spirit, the spirit that gave birth to the work that attracted attention throughout the world. Although our hours of conversations covered violin techniques, it was only when we talked of developing children’s innate abilities that his eyes lit up with a special vision. This was the leitmotif of his life. Shin’ichi Suzuki had studied for eight years in Germany with the celebrated violinist Karl Klingler before returning to Japan to concertise and join his musician brothers as first violinist in the Suzuki String Quartet. But the direction of his life changed when the father of four-year-old Toshiya Eto, destined to become a world-famous violinist, asked Suzuki to teach his eager young son to play the violin.

‘It was around 1931. I was teaching violin at the Imperial Conservatory to a class of mostly young men,’ Suzuki said. I didn’t answer Mr Eto immediately. I had to think. How would I train a small child? What would I teach him?’ As he was seeking answers to these questions, Suzuki suddenly realised the implications of an obvious fact and, in the middle of a quartet rehearsal, exclaimed excitedly, ‘All Japanese children speak Japanese!’ Seeing his brothers’ incredulous expressions he went on to explain the significance of his remark: if every normal child is successfully educated by the mother-tongue method, perhaps he could use the same approach to teach Toshiya to play the violin. The discussion continued well into the night. All four brothers had studied in Germany and shared the adult’s humbling experience of learning a new language.

They had great respect for children’s ability to learn to speak their mother-tongue so successfully. Suzuki’s mind was full of questions. ’Since learning to speak a language fluently requires high ability, and all children learn to speak their mother-tongue fluently, what does this tell us about children’s abilities? Should we not expect that they are able to learn other things as well? What about the methods used in schools where many of these same children fail to develop their abilities in other areas? Have these bright infants used up all of their potential for learning, or is there an enormous difference between the educational process found in the classroom, and in music training, from that found in the mother tongue approach?’

There followed detailed observation and study of the mother tongue process and of the innate capabilities that enable children to learn their native language so successfully. Suzuki found that all children have different rates of learning, most leaming very slowly at the beginning, and in very small steps. They learn only what they hear and from this develops the desire to learn. There is no stress or competition because children and attending adults expect the leaming to take place. Children seem to be fascinated by, and enjoy, the learning process. They are capable of a great number of repetitions, done with intense concentration, and things learnt are remembered because of their large capacity for memory recall.

What of the method itself? The mother-tongue method, Suzuki noted, is 100 percent successful with normal children, relying on aural models and requiring many repetitions, including continued constant repetition of learnt material. There is a high degree of motivation to speak and the learning seems effortless. Competition is not present, an amazing memory is nurtured, and the child determines when he or she is ready to begin speaking.

Suzuki observed the importance of the parents’ role during this learning period. They were the role models: in their speech, in their expectations and in their fascination with the learning process. Their understanding that the beginning stages are very slow and that the child matures at its own rate is very mportant. By their enthusiasm and joy, their constant, sincere encouragement and praise for each small step accomplished, they create the necessary nurturing environment needed for learning. They were encouraged to show the same joy at the small musical steps accomplished as they had when the infant learnt a new word.

Suzuki’s goal was to incorporate into his teaching as many of these characteristics as was feasible. Traditional musical instruction was woefully inadequate, he felt, compared to the mother tongue process. Investigating the early training of famous prodigies, he found many of the mother-tongue features present. When William Primrose visited Suzuki in Japan he realised his own early training was remarkably similar to that suggested by Suzuki. He told me he had been nurtured by devoted parents in an inspiring musical environment: ‘My father was a violin teacher and as a small child I would play quietly in his studio during student’s lessons. I wasn’t trying to absorb anything, yet when I came to use vibrato, for example, it came naturally without effort since I’d had so many aural and visual models.’

Suzuki was interested not only in training excellent musicians but in helping them develop into noble human beings through their musical training as well. Parents and teachers were told that first and foremost they must love the child and believe in his or her high abilities. ‘We should never underestimate the influence our attitudes have on our child’s development. The child senses that we truly believe that she has great potential and that we are fascinated and overjoyed with her development. From this she gets the confidence to grow. Daily we must remind ourselves that each child has high ability.’ Teachers were repeatedly reminded that children learn very slowly at the beginning, and that all children mature at different rates just as they did when they learnt to speak.

Since infants learn to speak before they learn to read, Suzuki taught them to play before learning to read. His book Note Reading for Violin (1956) showed that he did believe in teaching reading, but he delayed it until the child was able to play the Vivaldi A minor Concerto. Because of this delay, and few opportunities for playing chamber or orchestral music, students’ reading skills developed slowly in Japan.

In the West, Suzuki teachers now introduce music reading when the child’s bow arm, left-hand placement and general posture are well set. This coincides most often with their study of Bach minuets and other Baroque repertoire at the same level.

Along with the publication of his first books of study pieces a recording of the music was produced, Suzuki found that if the students listened to the recordings many times at home, they would have memorised the pieces before they began to study them. Therefore the learning process would be accelerated. This also produced what the educator Montessori called a ‘built-in error recognition’. It allowed the teacher to focus on tone and technique. ‘If you want your children to progress rapidly, increase their listening time. They will have the piece memorised before they play a note. Remember, your child learnt to speak by listening to you speak!’

Private lessons were a communal affair with students and parents coming early or staying late to watch and listen to other lessons. This could provide great motivation, Suzuki found, if the teacher really loved children and enjoyed teaching them. Creating learning games to make practice fun and presenting new material in small increments that would not overwhelm the child required careful planning by the teacher, who must always consider the age and readiness of the child. A teacher highly regarded by Suzuki told me, ‘When I realise the child is becoming discouraged, I say “Oh, I think I made a mistake and gave you too many new notes. Can you try just these few notes? Is that better?” The mother often looks as relieved as the child.’

At the private lesson difficult passages are introduced and etudes are created from the literature before the child begins study of a piece. Suzuki believed the student is motivated to practice if he knows where the practice is leading. To teachers, he stressed the importance of asking the child to correct or practise only one point at a time, so that learning would seem almost effortless.

Review of learnt pieces is an integral part of every private lesson. Suzuki complained that it was difficult for him to convince adults of the importance of review in spite of their knowing that infants grow in language fluency by repetition of words already learnt. The children actually learn to play with more fluency in the review pieces than with the new. This also improves musical memory and they ’are happy and confident when they can play many pieces for family and friends.’ Lessons varied in length according to the attention span of the child: ‘That is the reason why having several small children in the studio at the same time is helpful. Many beginning lessons are only five minutes in length.

Mothers understood they would be paying for a 30-minute lesson, five minutes of which might be with the child alone, a few minutes of unison playing with other children, ten minutes of instruction for the mother and the rest spent observing other lessons. Group lessons were added later, usually once a month, to allow children to experience the thrilling sound of many violins pllaying together. It was often in concert format, with the younger children playing what they knew and then sitting down to listen to the more advanced students. This was considered another great motivational source.

After variations on the familiar Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star which begin every child’s violin study, the first volume of the Suzuki violin books contains mostly folk songs and a few original pieces by Suzuki. The other volumes focus on traditional music of Baroque and Classical style. Supplementation was not a parallel to the singer’s ‘vocalisation’, so each violin lesson began with this tonal study.

‘There is a good or bad tone for every student level.’ Suzuki maintained. ‘Beginners should be encouraged to play with the most beautiful tone possible, like the sound of ringing open strings.’ This emphasis on beautiful tone was obvious to the audience at the Philadelphia debut when ten young violinists opened the concert with a performance of the Grave from Eccles’s G minor Sonata. Paul Rolland wrote that many in the audience were moved to tears by the sheer beauty of tone and phrasing in the performance.

Suzuki constantly experimented with the bow arm’s role in tone production as he tried to find a way to achieve a beautiful sound with least effort. As Suzuki began to have hearing loss, around 1973. he concentrated more on volume of sound. Consequently, he encouraged the use of a lower and lower elbow for more arm weight. Many teachers questioned this and chose to emulate his earlier demonstrations which represented a more mainstream violin technique.

Suzuki has often been criticised for saving that talent is not inherited. He was so passionate about the development of talent that he didn’t want any child to be stigmatised by being categorised as untalented - especially if the child adapted slowly to his environment at the beginning of training. In his book, Nurtured by Love, he wrote, ’The only superior quality a child can have at birth is the ability to adapt with greater speed and sensitivity to its environment’, and again, in an earlier work, Young Children’s Talent Education and its Method (1949), he wrote, ’Needless to say, there are innate differences among children, and therefore naturally there are differences in their ability, but instead of being obsessed by innate traits, society should change its understanding and; make efforts to raise every seed until it grows fine blossoms and fruit.’

When musicians complimented Yukari Tate on her splendid performance of the Chausson Poeme at the age of 14, she laughed and said, ‘1 was lucky to have Suzuki-sensei as my teacher. He didn’t give up on me even though it took me two years to leam the ‘Twinkle Variations” - I was a very slow beginner!’

One of Suzuki’s favourite aphorisms was ‘Ability breeds ability.’ During the year spent in Japan our six-year-old son Bill Jr. was enrolled in the Genchi Elementary School near our home. Teachers there told us they were delighted to teach children who were studying music in Suzuki’s Institute: They are sensitive to others, excel in everything they do and have a concentration level that far surpasses most of the other students.’

Our four-year-old son, Michael, studied violin and attended kindergarten at the Talent Education Institute. At the end of the year he was able to recite - in Japanese - more than 100 haiku along with the rest of his class!

The principle of Talent Education, based on the way we learn our mother tongue, will certainly change the course of education. No one will be left behind; based on love, it will foster truth, joy and beauty as part of a child’s character.

Shin’ichi Suzuki

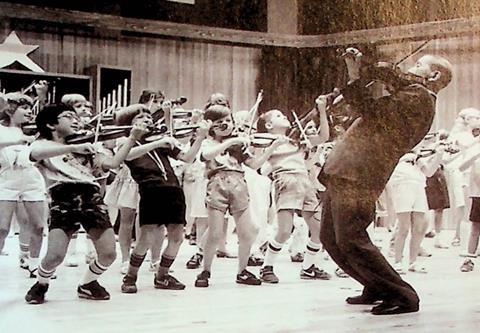

Suzuki gained the acclaim and respect of many famous musicians. In 1961, Pablo Casals came to Tokyo’s Bunkyo Hall to hear the children perform in concert. As the 400 violinists played the Vivaldi A minor Concerto and the Bach Concerto for Two Violins he wept openly. At the end of the concert he rushed to the stage shouting ‘Bravo’, threw his arms around Suzuki and wept on his shoulder. In a voice shaking with emotion, he spoke to the audience: ‘To train these children to understand that music is not only sound for dancing or to have small pleasure but such a high thing in life that perhaps it is music that will save the world - this is wonderful. I congratulate not only the teachers but all adults here. I give you my whole admiration, my whole respect.’

When the touring children gave a concert at New York’s Juilliard School, Newsweek wrote, ‘Playing without a conductor and using no scores, the youngsters were a living testimonial to the validity of Suzuki’s unorthodox teaching method.’ The violinist Ivan Galamian exclaimed, ‘This is amazing. They show remarkable training, a wonderful feeling for the rhythm and flow of music.’

Over the years Walter Gieseking, Yehudi Menuhin, David Oistrakh, Arthur Grumiaux and Leonid Kogan visited Suzuki and observed his work. At Suzuki Conferences in the US, Josef Gingold, Dorothy DeLay, Claude Erank and Janos Starker have been masterclass teachers of the young students.

The essence of Suzuki’s contribution to the world lies in two things. Because he believed in and loved young people, he was able to instill in many teachers and parents an unshakeable belief in the high abilities of all children and to inspire in them a passionate commitment to love them and nurture those abilities. ‘One day,’ wrote Suzuki, ‘the principle of Talent Education, based on the way we learn our mother tongue, will certainly change the course of education. No one will be left behind; based on love, it will foster truth, joy and beauty as part of a child’s character.’

Today, an estimated 400,000 children spread across all continents are reaping the benefits of that vision as they study violin, viola, cello, double bass, flute, piano, harp, recorder, guitar and voice, and in early childhood education programmes modeled on Suzuki’s kindergarten in Matsumoto. All are nurtured by their early childhood education.

Topics

Suzuki teaching: Every child can

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

Currently reading

Currently readingThe Suzuki method: A visionary with a violin

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet