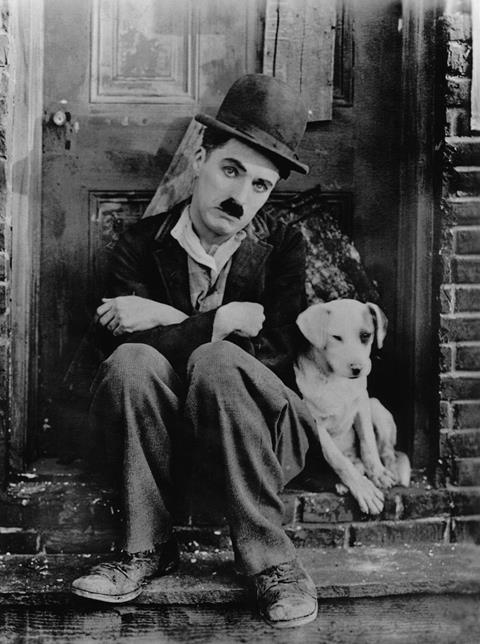

The great screen comedian, who died on Christmas Day, 1977, was an accomplished amateur violinist who composed many of the scores to his films. Ariane Todes looks at the central role the violin played in his life

At the height of his success, Charlie Chaplin harboured a fantasy about his violin. In 1920, shortly before the release of The Kid, he told a journalist: ‘I once had a day vision. I saw at my feet in a huddled heap all the trappings and paraphernalia of my screen clothes – that dreadful suit of clothes! – my moustache, the battered derby, the little cane, the broken shoes, the dirty collar and shirt. That day I had resolved never to get into those clothes again – to retire to some Italian lake with my beloved violin, my Shelley and Keats, and live under an assumed name a life purely imaginative and intellectual.’

It’s not surprising that someone who had risen from abject poverty to being the most famous man in the world in less than ten years might long for retreat, but I find the idea that Chaplin dreamt of taking his violin with him very touching. I’ve only recently come under Chaplin’s spell. I’d always disdained him, under the fashionable misconception that he was too sentimental. But then I discovered the whimsy, the childlike imagination, the anarchy, the grace, the humanism and the moral courage. Having consumed as many books, DVDs and live screenings as I could, I’ve become a Chaplin geek. And as I read, I discovered that Chaplin was a committed amateur violinist for much of his life, and that even when that passion abated, he poured the experience into writing string-laden film scores.

We have evidence of Chaplin playing on screen twice, in films that bookend his career. In The Vagabond of 1916, he plays a busker who is not above collecting other performers’ tips and who uses his violin to seduce a gypsy girl. There are a couple of lovely playing gags, involving a fourth finger that can’t stop trilling, and an itchy nose, and Chaplin ably demonstrates that any gag he can do (such as a chase and several falls into a bucket of water), he can also do clutching violin and bow. His playing looks fluid and confident, although his vibrato seems a bit tense, and his air of prim professional superiority, especially when bowing to his audience of one, is delightful.

Chaplin’s other violin performance comes in one of his last and most autobiographical films, Limelight (1952), in which he plays a faded music-hall star. His final performance is as a double act with Buster Keaton (who very nearly upstages him) on the piano, with Keaton trying to keep his music on the stand while Chaplin tries to adjust his own legs to the same length. When he plays, Chaplin’s look of needy ingratiation encapsulates the film’s main theme – the changing relationship between performer and audience over time. The sight of Keaton walking around with a smashed violin underfoot is possibly too painful to be funny (although it’s not as bad as watching Chaplin running around with his head stuck in a double bass in The Pawnshop). Chaplin is miming, but it’s a funny routine, and it’s poignant to see the two twilit masters together. It’s also interesting that (spoiler alert) Chaplin chose his fictional death to happen playing the violin.

Violin and cello are mentioned several times in Chaplin’s 1964 autobiography, a compelling account of the poverty and parental madness in which he was brought up in Victorian London. By the age of 16, he was already a rising talent in the English music halls and would practise his violin from four to six hours a day: ‘Each week I took lessons from the theatre conductor or from someone he recommended. As I played left-handed, my violin was strung left-handed with the bass-bar and sounding post reversed. I had great ambitions to be a concert artist, or, failing that, to use it in a vaudeville act.’

Stan Laurel, of double-act fame, shared lodgings and toured the US with Chaplin as part of Fred Karno’s music hall company in 1910. He backs up Chaplin’s claims, although he makes him sound somewhat pretentious: ‘He carried his violin wherever he could. Had the strings reversed so he could play left-handed, and he would practise for hours. He bought a cello once and used to carry it around with him. At these times he would always dress like a musician, a long fawn-coloured overcoat with green velvet cuffs and collar and a slouch hat.’ There is also a story that as Laurel cooked, which was forbidden in their digs, Chaplin would play the violin to cover the noise.

On his next tour of the US with Karno, in 1913, Chaplin was discovered by Mack Sennett of the Keystone Film Company, and from that point his rise was meteoric. In 1915 he was earning $1,250 a week at Essanay Studios and by 1917 he had signed with First National for $1,200,000, enabling him to build his own studio and allowing him unprecedented artistic freedom. In his autobiography he describes the moment his brother Sydney, who negotiated this deal, broke the news: ‘I had just taken a bath and was wandering about the room with a towel around my loins, playing The Tales of Hoffmann on my violin. “Hum-um, I suppose that’s wonderful.’’’

Through this most active of phases and arguably at the peak of his comedic powers, Chaplin still seems to have been practising regularly. A Mutual press release of 1917 emphasises the star’s commitment to the violin: ‘Every spare moment away from the studio is devoted to this instrument. He does not play from notes excepting in a very few instances. He can run through selections of popular operas by ear and if in the humor, can rattle off the famous Irish jig or some negro selection with the ease of a vaudeville entertainer. Chaplin admits that as a violinist he is no Kubelik or Elman but he hopes, nevertheless, to play in concerts some day before very long.’

Journalist Grace Kingsley was treated to Chaplin’s playing in 1918, writing: ‘He will permit you to sit in his dressing room, and let you do the talking while he affixes the horsehair to make up his moustache. You will notice a violin near at hand, also a cello. And it will be unusual if Charlie does not pick up the fiddle and the bow, and accompany your remarks with an obbligato from the classics, what time he will fix you with a far-away stare and keep you going with monosyllabic responses.’

Chaplin’s passion for playing seems to have gone cold by the time of a 1921 interview with the New York Herald, whom he told: ‘I used to play my violin a great deal up to a couple of years ago, but since then I’ve hardly touched it. I seem to have lost interest in such things.’ It seems that by this point his musical energies had transferred to writing film music.

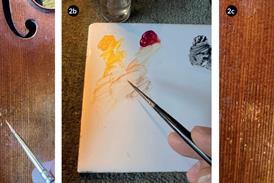

His interests in composing go back to 1916, when he started a music publishing company, releasing songs such as ‘Oh, that cello’ and ‘There’s always one you can’t forget’. It wasn’t successful, though, and soon closed. From City Lights (1931) onwards, he composed all his scores and went back in later years to write music for the older ones. Chaplin couldn’t read music and described the process of composing as ‘la-laing’ to musical associates, but he was involved in all the creative decisions about timing and scoring. Violinist Louis Kaufman played for several Chaplin soundtracks and in his biography describes Chaplin supervising every detail of the recordings and ‘creating little tunes and perfect themes’. Many of these themes became famous beyond the films, including ‘Smile’ from Modern Times and ‘Eternally’ from Limelight.

As in his films, Chaplin brings an instinctive sense of timing, structure and emotional persuasion to bear in his scores, and some of his most powerful scenes are accompanied by violin themes that fully wring the emotions. The heartbreaking ending of City Lights, for example, and the tumultuous high point of The Kid, when the young Jackie Coogan is taken by the orphanage director, are both accompanied by dramatic string mus

No comments yet